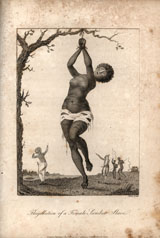

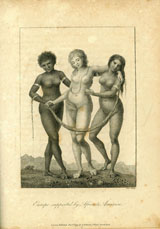

While slavery and the transatlantic trade in slaves had been topics of debate in the eighteenth century, the growing presence of abolitionists like William Wilberforce brought them to the forefront of public debate during the Romantic period and ultimately led to the passing of the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in March 1807. In print, works from Blake’s “The Little Black Boy” to Coleridge’s The Watchman, which ran several articles about slavery, addressed issues of empire and the racial violence that often went along with it. The images in these two cases exemplify two faces of empire and slavery: tyrannical subjugation and idealized intercultural dependence. It is particularly interesting that Blake seems to have portrayed the same woman in “Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave” and “Europe Supported by Africa and America.” In the former, the individual experiences of the young woman seemingly symbolize the horror of slavery. In the second image, she has become a personification of Africa. Stedman’s optimistic gloss to the engraving is undermined by the clearly hierarchic representation of the figures, which reflects racial ideologies of European superiority. Furthermore, the three women evoke the triangular trade, wherein European goods were sold in Africa, slaves were sent to America, and American goods were shipped back to Europe, with nations and individuals reaping bloodstained profits. The subtext, then, of Stedman’s system of “support” as portrayed by Blake is one of violent exploitation.

Blake’s engraving illustrates a scene of a young female slave receiving 200 lashes for “firmly refusing to submit to the loathsome embraces of her detestable executioner.” Stedman claims that after his conversation with the overseer about the woman’s brutal treatment he was so disgusted that he refused to have any further communication with men of that profession.

Engraved by William Blake from a drawing by J.G. Stedman.

J.G. Stedman. Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana.

London: J. Johnson, 1796.

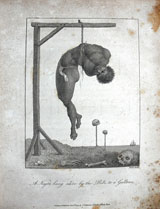

Throughout the Expedition, graphic engravings and Stedman’s equally vivid descriptions portray the shocking violence of slavery. However, despite his own mortification in response to these atrocities, Stedman cautioned against sudden emancipation for fear that the “perfectly savage” nature of Africans would make them incapable of governing themselves.

Engraved by William Blake from a drawing by J.G. Stedman.

J.G. Stedman. Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana.

London: J. Johnson, 1796.

This idealistic image, the final engraving in Stedman’s two-volume narrative, stands in stark contrast to the majority of the other illustrations in the work. Violence has turned to peaceful support, and the only reminders of slavery are the silver armbands on both Africa and America. Recognizing the disparity, Stedman writes: “I will close the scene with an emblematical picture of Europe supported by Africa and America, accompanied by an ardent wish that in the friendly manner as they are presented, they shall henceforth and to all eternity be the props of each other.”

Engraved by William Blake from a drawing by J.G. Stedman.

J.G. Stedman. Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana.

London: J. Johnson, 1796.