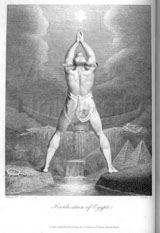

Egypt’s monuments, archeological artifacts, and ancient history fired the imaginations of people throughout the Romantic period: Blake’s engraving of 1791 expresses contemporary fascination with the country. Soon to follow was an explosion of Egyptian-inspired clothing, literature, and furniture. Fashion aside, the political documents Coleridge prepared for the de facto Governor of Malta, Sir Alexander Ball, demonstrate the more pressing concerns surrounding Egypt in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Napoleon’s invasion of the country in June 1798 undermined the economic and colonial stability of British India and brought the strategic role of Egypt to the fore. In 1804 when Coleridge was writing his “Observations” and the corresponding “Appendix,” there were fears that France would once again attempt to reoccupy Egypt. No longer simply a gateway to the East, the region was increasingly viewed as a desirable potential asset for Britain or alternatively, if under control of the French, a serious threat (which, in the event, never materialized). The symbols of fertility in Blake’s print carried over to political and economic realms, as Coleridge and others assessed possibilities of the systematic cultivation and exportation of goods from the Nile Valley to Europe.

The engraving “Fertilization of Egypt” was developed from a sketch of Anubis by Fuseli.

Designed by Henry Fuseli and engraved William Blake

Erasmus Darwin. The Botanic Garden, a Poem, in Two Parts. 3rd Edition.

London: J. Johnson, 1791.

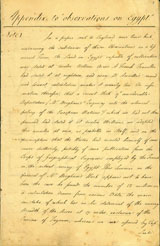

The eight leaves of the “Appendix” clarify and correct several arguments and statistics Coleridge had outlined in his earlier “Observations on Egypt,” both of which he prepared for Sir Alexander Ball. Among other points, the documents assert that, if colonized and cultivated, Egypt’s fertile land and “docile” native workforce could be used to support Europe.

“Appendix to Observations on Egypt.” (After 6 December 1804.)

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge but written in an unknown hand.